History is only a catalog of the forgotten.

(Henry Adams)

I’m still a slow learner. But let’s talk about witches.

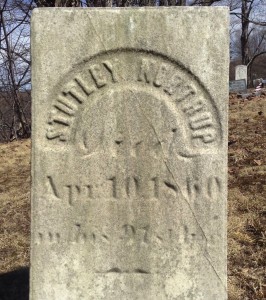

James Wakelee’s first appearance in the documentary record is 18 February 1640/41 O.S., when he is noted as owning four acres of land at Hartford, Connecticut (1) [Love, p. 127]. The last record, a court order of May 1691, part of his long struggle to free his assets from legal difficulties, mentions, off-hand, that he has died [Hoadly, p. 35].

Everyone knows about the witch craze of 1692–93 in and around Salem, Massachusetts, but few remember the earlier prosecutions. Towards the end of 1662, in Wethersfield, Connecticut, James was indicted for a capital crime; recognizing his peril, he abandoned his family and property and fled to Rhode Island [Adams, pp. 260-261]. That indictment has not survived, but a deposition from the later trial of Katherine Harrison for witchcraft mentions him:

Thomas Bracy aged about 31 years testifieth as follows that formerly James Wakeley would haue borrowed a saddle of the saide Thomas Bracy, which Thomas Bracy denyed to lend to him, he threatened Thomas and saide, it had bene better he had lent it to him. Allsoe Thomas Bracy beinge at worke the same day making a jacket & a paire of breeches, he labored to his best understanding to set on the sleeues aright on the jacket and seauen tymes he placed the sleues wronge,… and soe was forced to leaue workinge that daie.

. . . . .

After that Thomas Bracy aforesaide, being well in his sences & health and perfectly awake, his brothers in bed with him, Thomas aforesaid saw the saide James Wakely and the saide Katherin Harrison stand by his bed side, consultinge to kill him the said Thomas, James Wakely said he would cut his throate, but Katherin counselled to strangle him, presently the said Katherin seised on Thomas striuinge to strangle him, and pulled or pinched him so as if his flesh had been pulled from his bones, theirefore Thomas groaned. [Taylor, pp. 49-50]

This deposition, sworn before magistrates, must, in some sense, be true; Thomas Bracy was not lying. (2)

Now, such historical events as these, however minor (or, rather, historical texts, since what we can receive of the past is almost entirely textual) — such events might seem to bear their sense plain on their surfaces. But that’s not true, I think. Most of us nowadays would say: This man quarreled with me so that I could not concentrate on my work. But this 17th-century tailor said: He bewitched me! And we might say: I had a bad dream and my neighbor was in it. And yet these people said: He’s a witch! (3)

Why?

Of course, there can be no other subject than what we might call the real world, simply because there is no other subject. What then (for example (4)) is science fiction about? The real world. What is fantasy about? The real world. And witchcraft? Again, the real world. But the means that they have, science fiction or fantasy or witchcraft, (5) of going about being about the real world differ — and are as different from each other as from any other rhetorical mode.

A rhetoric is only the tekhnē (6) of discovering and framing a discourse: a method for abstracting from the real world our experience of it, or a means of expressing that experience. Witchcraft has its own distinctive rhetoric, basically a Manichean one, with virtue and evil contending in opposition for men’s (for these deponents were mostly men) souls. This James Wakelee, accused but escaped witch, was possibly one of my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfathers [Jacobus, p. 627].

Witchcraft is not merely rhetorical.

Nor is fantasy.

Nor science fiction.

Our own words pull our attention out of ourselves, away from what we know, or wish to know, for a while — a little while — to an imaginary world very like our own world (insofar as that world is not itself imaginary), only not, you know, not quite —

Not quite the same.

NOTES

1. He appears on the third list of the “Names of Such Inhabitance as were Granted lotts to haue onely at The Townes Courtesie wth liberty to fetch wood & keepe Swine or Cowes By proportion on the Common,” [Love, p. 125] probably as a result of efforts to attract useful trades to the settlement. James is recorded somewhere — I do not have the reference at hand — as having been a weaver.

2. That is to say, Thomas clearly harbors some animosity towards James, but he is not perjuring himself here. At this point, James has been living in Rhode Island for about seven years, interrupted by a year’s return to Wethersfield which ended with James again fleeing an indictment or the threat of one.

3. There’s more to it than that, of course. But the so-called witches of modern horror stories and movies have nothing, nothing whatsoever, to do with it, nor do the antics of those who call themselves witches nowadays. The standardized indictment for witchcraft sums it all up succinctly: “Joane Carrington thou art Indited by the name of Joane Carrington the wif of John Carrington that not hauing the feare of God before thine eyes thou hast Interteined familliarity with Sathan the great Enemy of God and mankinde and by his helpe hast done workes aboue the Course of Nature for wch both according to the Lawes of God, and the Established Lawe of the Common wea thou deseruest to dye” [Adams, p. 93].

4. Genre is a marketing category: where to send the ad dollars, which shelf to plunk the product on. At my local library, books one and three of Paul Park’s Roumania sequence were shelved in the science fiction section, two and four in adult fiction. When I pointed this out, the librarian asked where I thought they should go; I told her it hardly mattered, genre is arbitrary, but keep them together; and she gave me one of those why-do-I-always-have-to-deal-with-the-lunatics looks.

5. It’s probably important to point out here that this is not a question of definitions. The question is how, exactly, words trick us into believing, or temporarily consenting to believe, things that we know are not true, cannot be true, can never be true. There’s more than one way to pull off this trick. The various tricks, or sets of tricks, I am calling a rhetoric. Thus the rhetoric of fantasy is not the same as the rhetoric of science fiction, however we might choose to define those categories.

6. Greek τεχνη = art, skill, craft, trade, science; artifice, cunning, trick; work of art. That’s a good phrase to end this little essay with: science fiction stories are works of art.

WORKS CITED

Adams, Arthur, editor. Records of the particular court of Connecticut 1639-1663 (Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society Volume XXII). Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1928.

Hoadly, Charles J., editor. The public records of the colony of Connecticut, from August, 1689, to May, 1706. Hartford: Case, Lockwood and Brainard, 1868.

Jacobus, Donald Lines. History and genealogy of the families of Old Fairfield. Volume 1. Fairfield (Conn.): The Eunice Dennie Burr Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution, 1930.

Love, William DeLoss. The colonial history of Hartford gathered from the original records. Hartford: Privately printed, 1914.

Taylor, John M. The witchcraft delusion of colonial Connecticut 1647–1697. New York: The Grafton Press, 1908.