My longish story, “That We Maye with Free Heartes Accomplishe Those Thynges,” appeared not too long ago in Beneath Ceaseless Skies. As always with this series of historical fantasies, it all started with what little is known about one of my ancestors, in this case one Benjamin Blowers. Because it’s set in Georgian-era London and aboard a convict ship bound for the colonies, I ended up doing lots of thoroughly enjoyable research—although of course I didn’t feel bound to keep everything strictly accurate, plausible, or even possible.

Let’s begin:

Benjamin Blowers was born 22 December 1741 and christened 4 January 1741/2 (both dates Old Style) at St Martin-in-the-Fields, as recorded in the parish book indexed in “England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975,” a database maintained at familysearch.org. His parents are named as Jonathan and Mary of that parish. Jonathan was a victualler at Hungerford Market and a householder in One Tunn Lane (both places now buried under Charing Cross Station), where he sometimes let rooms to boarders; in 1751, and probably other years, he served as constable in the parish; and he was confined in Bridewell Prison, most likely for debt, for at least a portion of 1761, being listed on 12 April as owing 4 shillings 3 pence for bread distributions. Ben himself was prosecuted and convicted for an unspecified felony at the Westminster Quarter Sessions of January 1767 held in “Guild hall in King Street Westmr.” The prosecution was pursued by one Joseph Stephenson, a cordwainer of the parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields (according to a 1768 mortgage)—presumably, as was the custom of the time, because he was the victim. Stephenson was compensated 11 shillings for expenses incurred in the prosecution, and his receipt, dated 19 January 1767, is the only extant record of Ben’s trial. I examined these documents and others thanks to the superb resource “London lives 1690–1800: Crime, poverty and social policy in the metropolis” (londonlives.org).

The convict passenger list for the Tryall is printed in Peter Wilson Coldham, The King’s passengers to Maryland and Virginia, pages 194–196. The Virginia Gazette (23 April 1767, p. 2, col. 1) prints a letter from London noting that the Tryall left there 9 January 1767 “bound to Potowmack river in America, 82 convicts [Coldham lists 149 names], under sentence of transportation in Newgate.” An Admiralty pass issued 22 January 1767 records the destination as Maryland, and notes as well as the name of the ship’s master, the number of crewmen, and so on. I accessed the Gazette through the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s digital archive (research.colonialwilliamsburg.org), and found the pass in the Williamsburg Rockefeller Library’s microfilm copy of Admiralty records.

John Somervell was born 1726 into an ancient Scottish family that had immigrated to Maryland after the failure of the Stuart cause (George Norbury Mackenzie (editor), Colonial families of the United States of America, in which is given the history, genealogy and armorial bearings of colonial families who settled in the American colonies from the time of the settlement of Jamestown, 13th May, 1607, to the battle of Lexington, 19th April, 1775, volume 2, pages 691–693). This voyage of the Tryall was his first and apparently only posting as master on the Atlantic crossing.

Bampfylde-Moore Carew’s life story is recorded in The life and adventures of Bampfylde-Moore Carew, the noted Devonshire stroller and dog-stealer; as related by himself, during his passage to the plantations in America. Containing, a great variety of remarkable transactions in a vagrant course of life, which he followed for the space of thirty years and upwards, to which is appended, in my edition, a useful “Dictionary of the canting language.” (You’ve got to love eighteenth-century book titles, and I couldn’t resist citing them in full. Why are they so ridiculously long? Because at that time books were sold unbound, leaving it to the purchaser to have them bound to best suit their taste and budget. Thus the book’s title page had to do all the work that dust jackets do today, attracting the eye and giving a sense of the book’s matter and manner; in short, the title had to sell the book.)

The transportees’ song is quoted from James Revel’s The poor unhappy transported felon’s sorrowful account of his fourteen years transportation, at Virginia, in America. In six parts. Being a remarkable and succinct history of the life of James Revel, the unhappy sufferer who was put apprentice by his father to a tinman, near Moorfields, where he got into bad company and before long ran away, and went robbing with a gang of thieves, but his master soon got him back again; yet would not be be kept from his old companions, but went thieving with them again, for which he was transported fourteen years. With an account of the way the transports work, and the punishment they receive for committing any fault. Concluding with a word of advice to all young men.

For a sympathetic treatment of the Georgian homosexual underworld, I highly recommend Rictor Norton’s Mother Clap’s molly house: The gay subculture in England 1700–1830. The description of Mrs Gibbs’s premises quotes from the court testimony of Samuel Stevens, a constable who posed as an intimate acquaintance of an informer, concerning a visit he made to Mother Clap’s establishment on Sunday, 14 November 1725. The mollies’ song is quoted from A genuine narrative of all the street robberies committed since October last, by James Dalton, and his accomplices, who are now in Newgate, to be try’d next Sessions, and against whom, Dalton (call’d their Captain) is admitted an Evidence. Shewing I. The Manner of their snatching off Womens Pockets; with Directions for the Sex in general how to wear them, so that they cannot be taken by any Robber whatsoever. II. The Method they took to rob the Coaches, and the many diverting Scenes they met with while they follow’d those dangerous Enterprizes. III. Some merry Stories of Dalton’s biting the Women of the Town, his detecting and exposing the Mollies, and a Song which is sung at the Molly-Clubs: With other very pleasant and remarkable Adventures. To which is added a key to the canting language, occasionally made Use of in this Narrative. Taken from the mouth of James Dalton., a pamphlet issued anonymously.

The Princess Serenissima is very loosely based on John Cooper, an unemployed gentleman’s valet, known as the Princess Seraphina. See Rictor Norton’s essay “‘Princess Seraphina’ steps out at Vauxhall Gardens,” vauxhallhistory.org/princess-seraphina-at-vauxhall-gardens, and Mother Clap, pages 156–160.

The Baron is loosely based on Pierre-François Hugues, called Baron d’Hancarville, who was, however, in Naples in 1766, cataloguing Greek vases for William Hamilton, the British ambassador. He did later take up residence in London before being driven abroad again by scandal and debt. He published a book of pornography lightly disguised as scholarship, Monumens de la vie privée des ouze césars, d’après une suite de pierres et médailles, gravées sous leur règne, in Nancy (France) in 1780; a scanned copy is available at the Hathi Trust (babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=gri.ark:/13960/t3nw0t47k). The best biographical source is Francis Haskell’s essay “The Baron d’Hancarville: An adventurer and art historian in eighteenth-century Europe,” reprinted in Past and present in art and taste: Selected essays, pages 30–45. The Baron’s speech on ancient morality quotes and paraphrases a few pages of Edward Ryan’s The history of the effects of religion on mankind; in countries ancient and modern, barbarous and civilized, but turns the sense of the quotation on its head, making a paean out of a vicious condemnation. See also Rictor Norton’s “Homosexuality in eighteenth-century England: A sourcebook of primary documents” (http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/index.htm).

Walter Stern’s exhaustive history The porters of London was invaluable for details (most of which I’ve omitted) of the business of transporting goods by hand, as was Johnstone’s London commercial guide, and street directory; on a new and more efficient principle than any yet established for the particulars and locations of various establishments.

The description of shoe-black boys and most of the street cries are quoted from Charles Hindley’s A history of the cries of London, ancient and modern. George’s first poem is adapted from “The vain dreamer” in John S. Farmer (editor), Musa pedestris: Three centuries of canting songs and slang rhymes (1536–1896), pages 46–47.

The text of the handbill that George finds in the mud was cobbled together from several of Mrs Cornelys’s advertisements in period newspapers for her entertainments at Carlisle House. George’s second poem is slightly adapted from “The poetess’s bouts-rimés” in Roger Lonsdale (editor), The new Oxford book of eighteenth century verse, p. 414.

The account of Carlisle House’s interior arrangements is partly dependent on the journal of Samuel Curwen, quoted in F.H.W. Sheppard’s Survey of London, volume 33, “Soho Square Area: Portland Estate, Carlisle House, Soho Square.” The costumes present are drawn from the article “An account of the masquerade at Mrs. Cornelys’…” in The town and country magazine, or universal repository of knowledge, instruction and entertainment, March 1770, pages 118–119. The first meeting of her Society in Soho-square this year did not actually take place until 20 November (Gazetteer and new daily advertiser (London), 21 October 1766).

Ben’s shipboard tale is also drawn from Life and adventures. Some of Ben’s remarks in the hold are adapted from Henry Mayhew, London labour and the London poor, volume I, page 48.

The opening paragraphs of the Covent Garden scene are based on, and partly quote from, Hell upon earth: Or the town in an uproar: Occasioned by the late horrible scenes of forgery, perjury, street-robbery, murder, sodomy, and other shocking impietie, pages 8–10. Dan Cruickshank’s The secret history of Georgian London: How the wages of sin shaped the capital and M. Dorothy George’s London life in the eighteenth century together provide an exhaustive account of Georgian London’s street life. Thomas Beddoes’s public demonstrations of pneumatic medicine (and subsequent craze for the same) actually occurred some thirty years later—he was six years old at the time of our story—although on 29 May of this year (1766), Henry Cavendish presented his paper “On Factitious Airs” before the Royal Society.

The first stanza of George’s third poem is adapted from “A Remonstrance” by John Gerrard (floreat 1769), and the second stanza from “The Emulation” by Sarah Fyge Egerton (1669?–1722), both to be found in Eighteenth century verse, pages 554 and 37. The chatter about current events relies on The annual register, or a view of the history, politics, and literature, for the year 1766, fifth edition (1793), pages 149–151. Pomegranate Molly’s remark about the miasma is paraphrased from Vitruvius’s De architectura, I.4.1.

The description of Ben and the Baron’s meal draws on John Timbs, Clubs and club life in London: with anecdotes of its famous coffee houses, hostelries, and taverns from the seventeenth century to the present time. An account of Mr Drybutter, his shop, and his misadventures may be found in Rictor Norton’s essay, “The Macaroni Club: Homosexual scandals in 1772,” rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/macaroni.htm, and Mother Clap, pages 311–317.

The Baron’s remarks on art rely on snippets of d’Hancarville’s introductions to volumes 2 and 3 of his Collection of Etruscan, Greek and Roman antiquities from the cabinet of the Hon. W. Hamilton his Britannick Maiestys envoy extraordinary and plenipotentiary at the court of Naples. The jokes (rather mirthless to modern ears) about macaronies are lightly paraphrased from The macaroni jester, and pantheon of wit; containing all that has lately transpired in the regions of politeness, whim, and novelty. Including a singular variety of jests, witticisms, bon-mots, conundrums, toasts, acrosticks, &c.—with epigrams and epitaphs, of the laughable kind, and strokes of humour hitherto unequalled; which have never appeared in a book of the kind.

The visit to Bedlam draws on Ned Ward’s description in The London spy compleat and Edward Geoffrey O’Donoghue’s monograph The story of Bethlehem Hospital from its foundation in 1247. The speeches of the Baron’s mad-act are based on the pamphlet l’Art de péter, essai théorie-physique et méthodique, à l’usage des personnes constipées, des personnages graves & austères, des dames mélancoliques, & de tous ceux qui font esclaves du préjugé. Suivi de l’histoire de Pet-en-l’air & de la Reines des Amazones, où l’on trouve l’origine des vuidangeurs. The rantings of his neighbor derive from the famous delusions of James Tilley Matthews as recorded by John Haslam in Illustrations of madness: Exhibiting a singular case of insanity, and a no less remarkable difference in medical opinion: developing the nature of assailment, and the manner of working events; with a description of the tortures experienced by bomb-bursting, lobster-cracking, and lengthening the brain.

A full moon fell on December 16, 1766. George’s final poem is adapted from the poem by Anonymous, “Ignotum per ignotius, or a furious hodge-podge of nonsense: A pindaric,” Eighteenth century verse, p. 61. Emily Cockayne’s Hubbub: Filth, noise and stench in England, 1600–1770 offers invaluable data about city lighting at night, as well as of many of London’s other, less savory aspects.

George and Ben’s route from Bonds Stables to Distaff Lane may be traced on the anonymously published map, A plan of the CITIES of LONDON and WESTMINSTER and BOROUGH of SOUTHWARK with the new buildings, 1767 (mapco.net/anon/anon.htm). I’ve also consulted John Rocque’s more detailed 1746 map A plan of the cities of London and Westminster, and borough of Southwark; with the contiguous buildings; from an actual survey, taken by John Roque, land-surveyor, and engraved by John Pine, bluemantle pursuivant at arms, and chief engraver of seals &c. to his Majesty (hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g5754l.ct004187). The description of the Air-Loom is roughly based on the plate in Haslam.

The newspaper account of the fire is lightly adapted from The annual register, pages 153–154.

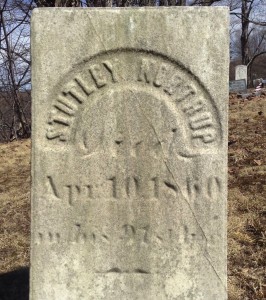

I have not been able to trace the Tryall’s arrival in America—certainly she did not call at Annapolis or Alexandria, and the Baltimore port records for that period are lost. But the Maryland Gazette (7 June 1770, p. 3, col. 1) prints “A LIST of LETTERS remaining in the POST-OFFICE, June 6, 1770,” including one for “Benjamin Blowers, Elk-Ridge Landing,” so presumably he was sold and was then serving his indenture in that area. The Gazette may be read online (msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/html/mdgazette.html), although it is not indexed. Benjamin Tasker’s speeches and the oath he requires of Somervell are adapted from a proclamation printed in the 9 July 1767 Maryland Gazette and from letters printed in the 30 July and 20 August issues, signed A.B., “Philanthropos,” and C.D., so this scene is slightly anachronistic, taking place as it must sometime in late March or possibly early April, 1767.

The snake-swallowing act is described in Mayhew, vol. III, pp. 117–119—a nineteenth-century record, but the performance was probably not then a novel one.

And, finally, the auction scene is based on The sufferings of William Green and the Old Bailey sessions papers quoted in Peter Wilson Coldham, Emigrants in chains: A social history of the forced emigration to the Americas of felons, destitute children, political and religious non-conformists, pages 120-21.